- James Donaldson’s Newsletter

- Posts

- Allowing Time to Master Your Working

Allowing Time to Master Your Working

New Post From James Donaldson

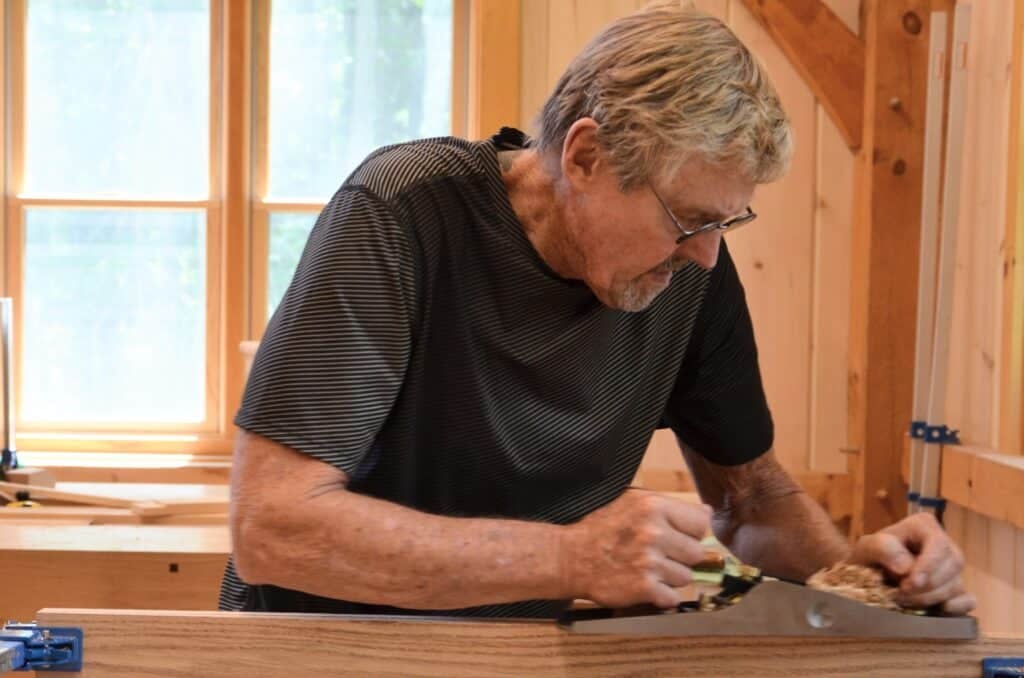

Growing woodworking skills to become an owned and well-earned craft takes time. For hand tool woodworking there is no substitute. With hand tool woodworking you cannot extract yourself from the whole high demand process by sending wood along fences, into power feeds or along alignment jigs like power router guides that cut dovetails in place of us. The sensory essentiality is magnified a thousand fold in the same way walking, sport like rock climbing, hiking the wildernesses cannot ever be matched by a video for the total reality of the immersive experience. Try to explain to the video watcher your slipping into the upper reaches of the Dry Frio river for a wild-water swim and all you will see is the eyes glaze over with the thought of, well, all that effort.

For those choosing the harder climbs, the steeper rides, the longer distances, the rewards are phenomenal. Yes, it’s demanding, but who is the one demanding it but us as individuals. These high-demand levels through self-discipline and self-development are no different than they would be for sports training, research, self-education and very much more. Those who rise to the top in just about any discipline you care to name got there by high levels of self demand and self discipline. They chose the path, stuck to it, lived it, came through the hard and often gruelling pinch points and all to gain the ultimate mastery all skilled work demands. We do what we do because we live for the uniqueness no other means gives us. It soon becomes clear that sharpening, accurate layout, dextrous hand skills and then, above all, exercising the whole body and mind, results in becoming a master. But this is a positive endeavour if we have the right attitude in our life choices in the work we carry out. Without even noticing, we find ourselves living for every difficulty. The fulfilment of hand making becomes our second-to-none moment when we must flex to absorb the rougher fibres with the surface cut of our plane’s cutting edge. The needs switch moment by moment and we find ourselves then shunning the filters of industry that otherwise separate us from engaging more fully with both the wood and tools to work it.

You and nature are conjoined, then there is no industrial processing to make what we make be that making a wooden ladle, a coffee table or the mirror frame. As I just said, establishing skill takes some practice, but experience has proven that everyone can cut a good dovetail and plane wood dead square with nothing more than #4 bench plane like a Stanley with its thin iron and ordinariness. With the right instruction and some dedicated time to learn everyone can match my skills and even better them. Spend four hours a week making for a few months and within a year you should be able to make everything I make using only your two hands and a two dozen hand tools max.

Often enough, I find myself explaining that most under say 40-year-olds sadly progressed through periods of neglected upbringing when it came to early mentoring in working manually. That’s the power and dynamic culture has on everything we do from sleeping to eating to working and being entertained. Because of that, owning parents that may never have seen much of or been involved in manual work, and then specifically the use of hand work in craft, the more hidden benefits such as skill may seem not to offer much of real value to their children. Today, we find so many would-be hand workers in craft came to it much later and as late-starters never had the benefit of owning such benefits early on in life. Add to that that so little is in fact crafted by humans these days, we see a dearth of places and spaces to practice almost any art except at the most novice levels. Thankfully though, the craft of woodworking in all of its many diverse areas is safe in the hands of amateurs and these are indeed the ones who carry the treasures with them in their home workshops. Those pursuing craft of hand work often came to it and now come to it through personally feeling the lack of multidimensional methods of working in their lives. What I have described through the years as amateur woodworking, what others call hobby woodworking, is nothing less than a driven force in the desire to make and to make mainly if not wholly by hand. There is something true and non-fanciful about it. Something non-fantastical in it. It’s simply applying the honesty of manual work to your life that fulfils the the creative in us. Personally, for the main part, I can’t imagine a life in non-making realms and when we feel the interest stirring then there is a dynamic that just makes things, even the impossible, happen.

Doesn’t matter what your lifetime work has been, in this case a psychologist pressing through the barriers brings achievements we might otherwise never have thought ourselves capable of.

I have learned though that rarely is it ever too late even though ideally the age of apprenticing should be between the ages of 12 on up to the late teens. It’s unlikely that anyone is looking for an apprenticeship in woodworking these days as the market for goods is so tight and competitive it can be hard even to think of making a living from any kind of craft work. But people are looking for good training and I don’t mean entertaining videos of someone skilled showing off. For most today, true and bona fide apprenticing (if we want to call it that) will never be an option. I think it is fair to say that most people will have had minimal if any exposure to the kind of manual or craft work I speak of. Our culture is such that it’s now the majority of under 30-year-olds who have no experience of work extending much beyond their keyboards. This too should not be dismissed as it is also skilled work but of an utterly different type and dimension. It’s not hard to work out why. Though neither would be considered manual skills nor manual labour, they both require dexterity that comes through rote repetition with regular maintenance exercise. I doubt anyone could survive too well without computer skills to direct the machines that make. Spectating sport seems to be much more highly considered than the arts and crafts fields once offered by most cultures. In my early teens I was forced to take part in sport and so chose long distance cross country because no one else did. It worked until I could finally quit school and start work. Unfortunately, I was a reasonable cricketer and footballer so was picked for teams in school but I would rather have been in woodworking and metal working venues rather than chasing a 9″ ball around a field for an hour. Oh, well!

Because starting our craft now comes quite later on in life what I’d learned by aged 16 doesn’t happen until higher education and worklife is well and truly established. But we amateurs shouldn’t in any way despair. We all were built to make. By that I mean our brains and bodies have all we need to take anything we care to name from the raw and make what once grew and convert it by craft into something functional and fine. We can do it at any age as long as we are reasonable healthy and have a mind to. It’s as simple as that.

Starting any craft late means waking up the dormant or latent untapped resources within every part of our being, often believing the opposite to what our mind might be saying in the privacy of our minds. Our sensory perception and receptors will gradually come alive within us as we explore the thing that excited us as a thought to get started. This genesis kick-start begins a process as we take those first evolutionary steps. Bar none, we were all undoubtedly born with ability to make. Your hands and bodies were designed to that end but that ability, when and if left dormant and denied for whatever reason, will initially feel to be more awkward than natural and so the outcome of first works might not match the ambition that triggered our move. Untapped during the more formative years of life is usually no more than a basic delay in development. Unfortunately you might well need a little more patience in achieving the results you hoped for starting out. Don’t believe it when you think you will never cut a straight line with a saw or plane two faces dead on 90º one to another. It takes training to achieve such things––training and self discipline. And don’t worry. I never met one of my 6,500 hands-on students that didn’t make great projects. The importance of getting the foundation right is critical. I’ve been working on this for three decades to date. My first class back in 1990 gave me the burden. I never stopped my personal making though. Alongside my more industrious making in business and training others, I held classes evenings and weekends pretty much throughout each of those three decades. Believe it or not, when we were building the two cabinets for the Cabinet Room of the White House, I held two classes with 15 students on board who knew nothing of why two stately pieces on support bases were for.

Your future, just like mine, is more a rite of passage into a better understanding of your craft and therefore, rather than over-expecting the premium results the teacher or master always seems to have you see the need to learn by doing. This is not an overnight thing. If we just take our time we will avoid having sensory overload and not fail under the pressures achieving the results we strive for. I liken this to being placed in a manual car with gauges in front to read and make decisions on whilst engaging the gears with the gear shift according to the numbers, using the clutch, brake and accelerator and then steer between oncoming cars and in three lanes on a high speed motorway. Watching the simulator is not the same as driving the real thing even though with 3-D glasses on it can feel close. We might think that we see and feel everything and well we might. That’s not the point. The point is what do we do with all of the information feeding into our brains through our receptors wherever they are? That first hour in the car is soon forgotten as we increase our experience in driving through subsequent hours. Eventually driving becomes as natural to us as walking and breathing. I never question whether my dovetail will come out or if my plane and spokeshave will smooth and shape my coarse-grained wood. I can usually consider other things with my mind still making decisions according to sensors transmitting relevant information to guide me in using my tools. This new-found freedom came to me in my later teens. In the same way I no longer consider how I hold my pencil or pen when I am drawing or writing, I am free to compose and make happen what couldn’t happen without it. My mind is ever-searching the grain for answers and the answers always come in the course of my day.

P.S. Don’t forget to get my entire collection of woodworking plans-HERE

-James Donaldson